Allisonians and the Halifax Explosion

University archivist explores stories of survival, loss, and giving back

Dec. 6 marks the 100th anniversary of arguably the worst tragedy to take place on Canadian soil.

Dec. 6 marks the 100th anniversary of arguably the worst tragedy to take place on Canadian soil.

On the morning of Dec. 6, 1917, more than 1,900 people were killed as a result of the Halifax Explosion. The final death toll was well over 2,000, around 9,000 more were injured, and almost the entire north end of Halifax — 325 acres — was destroyed.

“Despite the horror of that day, there remain stories of remarkable courage and survival,” says University Archivist David Mawhinney.

Mawhinney has found a number of Allisonian connections to the Halifax Explosion.

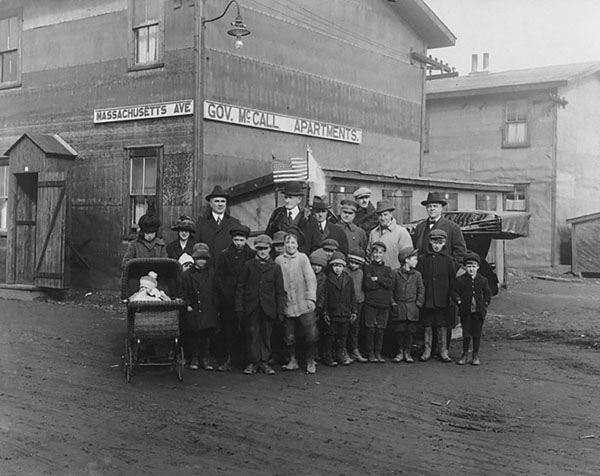

The University’s first chancellor, Ralph Pickard Bell (1907), for whom the University’s library is named, played a significant role in the aftermath of the explosion. Bell was appointed to the Halifax Relief Commission, established by a federal Order-in-Council to oversee the distribution of $21 million (the equivalent to more than $335 million in today’s dollars) pledged by government and members of the public following the disaster.

The Commission’s main goals were to create temporary shelter for those displaced by the explosion, to rebuild the community, and to ensure that those who were maimed or injured received pensions.

The Commission’s main goals were to create temporary shelter for those displaced by the explosion, to rebuild the community, and to ensure that those who were maimed or injured received pensions.

Then there is the incredible link between Ethel J. Bond, who graduated from Mount Allison in 1911, and Dorothy Swetnam. Swetnam was just six years old at the time of the explosion, but would go on to graduate with Mount Allison’s Class of 1933.

Then there is the incredible link between Ethel J. Bond, who graduated from Mount Allison in 1911, and Dorothy Swetnam. Swetnam was just six years old at the time of the explosion, but would go on to graduate with Mount Allison’s Class of 1933.

Bond was living in Halifax with her father and her sister Bertha in December 1917. She had already suffered a personal tragedy that year — in July her fiancé, Frederick Hockin, was killed in action while serving with the Canadian Infantry in France.

Bond’s father was killed in the explosion and their home was destroyed.

“It may be beyond my power of thought to collect enough to put on paper but I want you to see my hand writing first because that may convince you that I am all right,” Bond’s sister Bertha wrote to a friend after the explosion. “Both Ethel and I had a most miraculous escape and for that we are so thankful, but Sandy, when we got out of the house and found our dear dad, we — I can’t describe the sensation I had. He had just gone to the mill to get some sugar, which was in a barrel inside the door, and there we found his body. Our greatest comfort is that his death was instant and that he was ready to go.”

Swetnam was at home with whooping cough on the day of the explosion.

“She was listening to her mother play the piano for her brother Carmen’s upcoming Christmas solo,” Mawhinney says. “The explosion killed them both in an instant.”

Swetnam was trapped in a corner of the room.

“[We] finally landed at the parsonage,” Ethel’s sister recounts in her letter. “I didn’t expect to find a soul there, but I did. Little Dorothy was unhurt, but so completely hemmed in that her father was doing his best to saw her out. The other two were gone… By now the fires were blazing in pretty good shape… I’ll never forget Mr. Swetnam’s look when he saw us and if (Ethel and I) hadn’t gone she’d never in this world have been saved.”

Swetnam went on to complete a music degree — she and a classmate received the second and third Bachelor of Music degrees awarded at Mount Allison.

“Her life was dedicated to the creation of good music,” Mawhinney says.

After she graduated from Mount Allison she taught in the Music Conservatory for a year, then travelled to Japan where she headed the piano department at the Canadian Academy in Kobe. She was forced to leave in 1941 because of the Second World War and returned to teach at the Mount Allison Conservatory and School for Girls where she met and married fellow faculty member Clayton Hare. Swetnam died in Calgary, AB in 2002.

After she graduated from Mount Allison she taught in the Music Conservatory for a year, then travelled to Japan where she headed the piano department at the Canadian Academy in Kobe. She was forced to leave in 1941 because of the Second World War and returned to teach at the Mount Allison Conservatory and School for Girls where she met and married fellow faculty member Clayton Hare. Swetnam died in Calgary, AB in 2002.

Bond moved to Winnipeg at some point after the explosion on the invitation of a former Mount Allison roommate. The roommate was struggling with tuberculosis and asked if Bond would come to care for her and assist in her job conducting social welfare in the city.

Bond eventually pursued a diploma in social welfare at the University of Manitoba. She also renewed a friendship with Harold M. Hockin, the younger brother of her fiancé. They were married in 1919 and lived the balance of their lives in Winnipeg.

Allisonians continue to forge connections with the event.

The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax is currently exhibiting a piece by artist Laurie Swim (’71), who created a quilt commemorating the Halifax Explosion. Swim came up with the idea for Hope and Survival: The Halifax Explosion Memorial Quilt exhibit in 2000. The community art project, which includes a scroll of remembrance with names beaded in English and Braille, was completed this year.

In another example of things coming full circle, Swim was inspired by Janet Kitz’s book Shattered City: The Halifax Explosion and the Road to Recovery. When Mawhinney worked for the Nova Scotia Archives, he was given the task of processing Kitz’s papers where she recorded first-person interviews with explosion survivors.

“Those were some of the most difficult records I have ever processed in my career in archives,” Mawhinney says. “I was amazed at the distant way that many described the events of that day and what they had seen. It was as if they were transported back to their state of shock and disbelief. They talked about the events in the most clinical of terms. I remember asking my boss to give me something else to work on at the same time because it was too challenging to work on for a full day.”

In researching Mount A connections to the explosion, Mawhinney also notes that local people pulled together to support the survivors of the disaster.

On the day of the explosion the Sackville Town Council voted to use $500 for the purchase of provisions that would help those in need in Halifax. It also sent a team of six carpenters and glaziers to help in the days after the explosion and offered up local homes and the barracks as temporary shelter, though most survivors elected to remain in Halifax. Dorchester Council sent $250, the local boy scouts collected food and other donations, and local women’s organizations collected a significant amount of money, clothing, and other needed items.

A number of local women, including graduates of the Ladies’ College and Dr. H. R. Carter of Port Elgin, also travelled to Halifax and Truro to offer medical assistance in the immediate aftermath of the explosion.

“Certain events in history are etched into our memory. People remember where they were when Kennedy was shot or on 9/11,” Mawhinney says. “The Halifax Explosion was one of those events — something so big it becomes part of our collective consciousness.”

Photo captions:

Aftermath of the Halifax Explosion (Mount Allison Archives)

Ralph P. Bell, second adult from the right, with members of the Halifax Relief Commission and local children during Massachusetts Governor Samuel W. McCall’s visit to Halifax in November 1918. McCall was visiting an apartment block named after him on Massachusetts Avenue. (Nova Scotia Archives)

Ethel Bond, first on the left in the back row, with the Mount Allison 1910-11 YWCA Cabinet, helped to save six-year-old Dorothy Swetnam on the day of the Halifax Explosion. Dorothy would go on to study at Mount Allison as well. (Mount Allison Archives)

Dorothy Swetnam (Mount Allison Archives)

You can also hear David on CBC Radio (Moncton) sharing stories around the Halifax Explosion: http://ow.ly/6skL30h3nTO