An educator with a vision

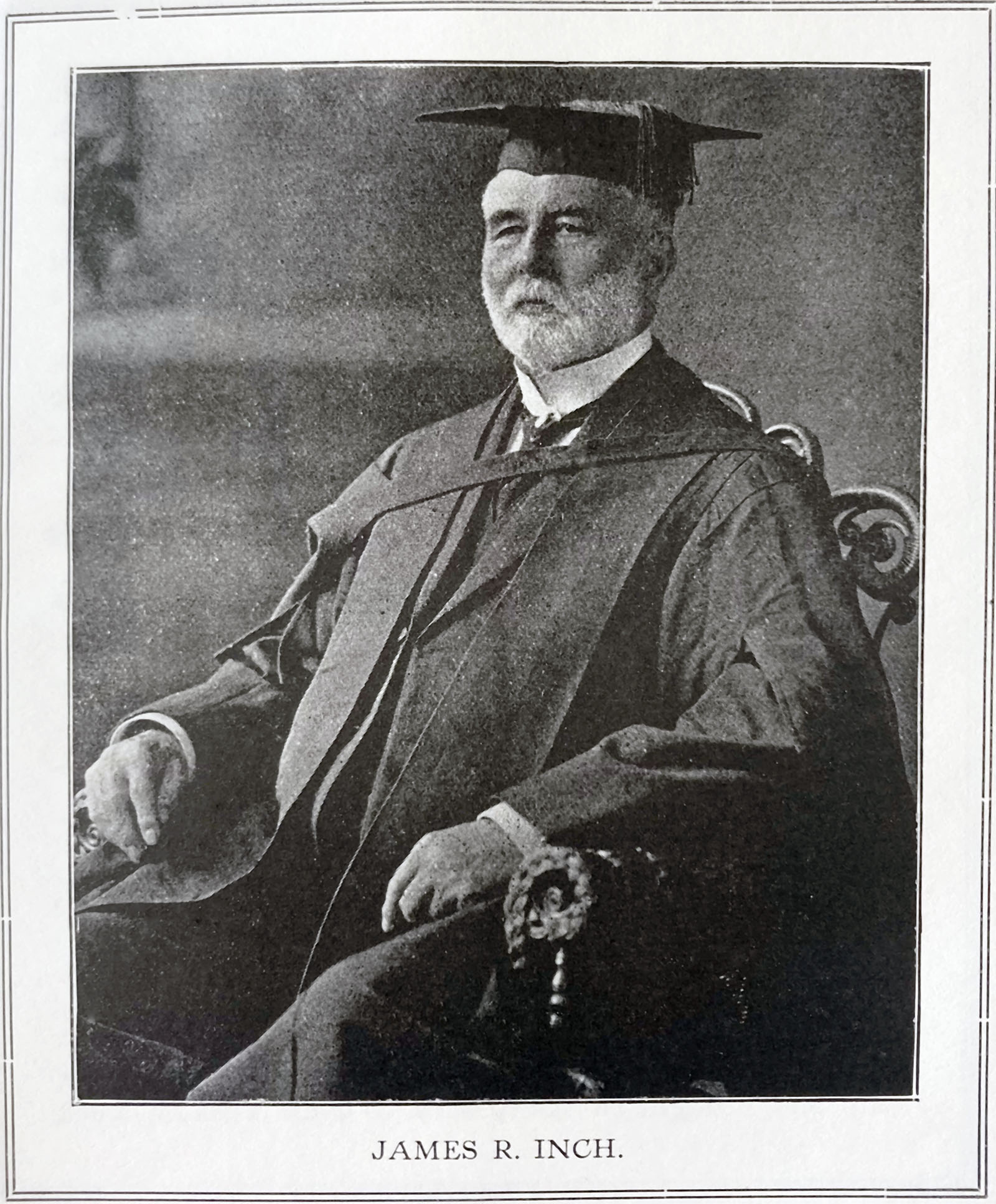

In 1872, James Robert Inch, principal of the Mount Allison Ladies’ Academy, proposed a motion to the Board of Regents that women be admitted to the University. As a result of his vision, Mount Allison University made history three years later by awarding the first Bachelor of Science degree to a woman — Grace Annie Lockhart — in the British Empire.

My great-uncle believed that “women students met with equal success with men.” His conviction was based on his long experience as a teacher and administrator. That experience began in 1850, when he was just 15 years old, and culminated in his service as the third president of Mount Allison University and later as the Chief Superintendent of Schools for New Brunswick.

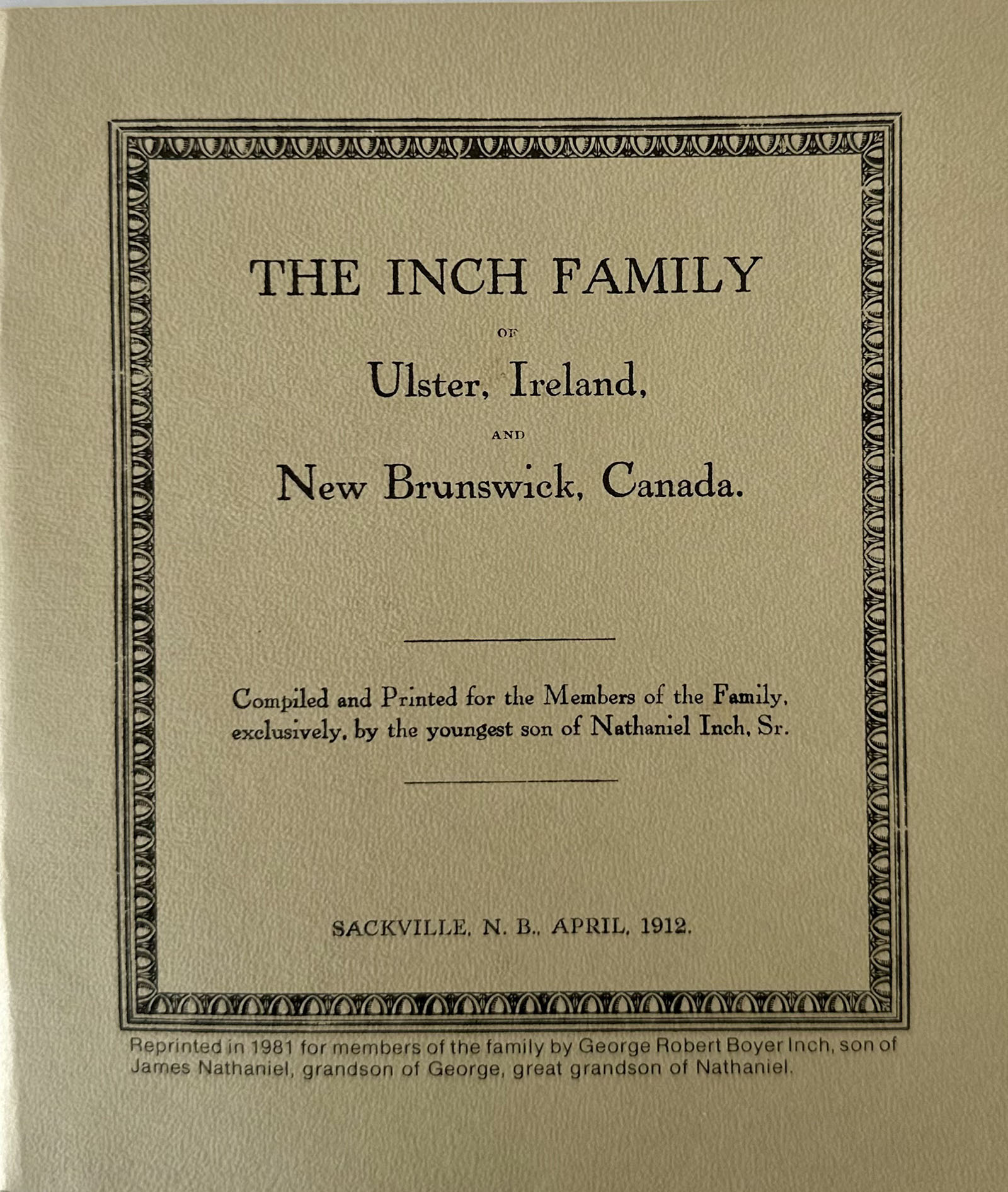

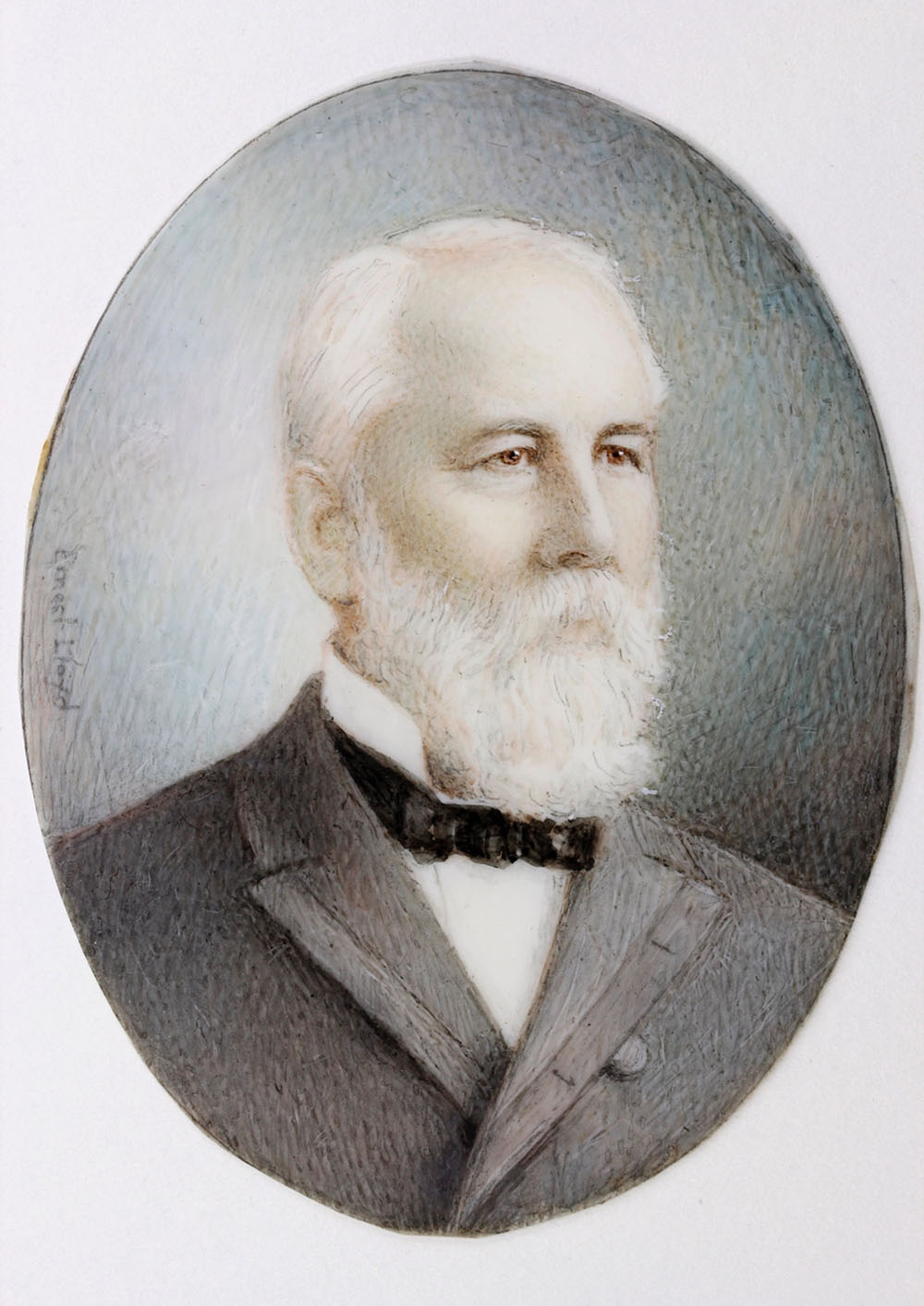

One could certainly call his beginnings humble. James Robert was the youngest of nine children, born in 1835 to parents who had immigrated from Ulster, Ireland, to Saint John, New Brunswick, a decade earlier. In his 1912 history of the Inch family, he wrote that they settled on 300 acres of wilderness in what was then called New Jerusalem (now part of Canadian Forces Base Gagetown), about 10 miles back from the Saint John River.

The land he bought was unbroken forest, and the first trees cut down were used to build the house in which the family lived for 20 years.

There were no roads — only bridle paths cut through the forest — and few mills to grind their grain or supply lumber. To get supplies, they had to walk ten miles to the river and row or sail about 30 miles to and from Saint John.

James Robert was educated in district schools in New Jerusalem — one of them likely Inchby School — and later at the Gagetown Madras School. The goal of the Madras system was to expand access to education by having senior pupils teach younger ones. Perhaps this is where my great-uncle decided to become a teacher.

At age 14, he entered the New Brunswick Normal School in Saint John. In his journal, he wrote about giving his first practice lesson: “I confess that when I mounted the stand, I felt pretty well alarmed. Before me were about 25 [student] teachers, each with a pen ready to take down any mistakes I should make. I was on the point of giving up, but the sense of disgrace it would be gave me fresh courage. I proceeded manfully.”

A deeply religious man throughout his life, most of his diary entries describe the sermons of Methodist and Baptist ministers and include numerous biblical quotations. He also referred to lessons on geography, algebra, sugar production, and the nations of Holland and Belgium.

He took his six-hour examination in December 1849 and began teaching in the Parish of Greenwich in January 1850. That July he was at home studying, though he worried “it [was] useless.” His concern was unfounded — he obtained a First-Class Teaching License that August and began teaching in public schools that September.

Four years later, my great-uncle accepted a position as a teacher at the Mount Allison Wesleyan Academy. He quickly gained a reputation as a popular and respected educator who was always ready to challenge his students.

Over the next 14 years, he served as vice-principal and then principal of the Ladies’ Academy. Recognizing the potential of women to succeed in higher education, he proposed that women be admitted to the University — a proposal approved by the Mount Allison Board of Regents. Soon after, Grace Annie Lockhart made history as the first woman in the British Empire to earn a Bachelor of Science degree.

During his time at the Ladies’ College, he earned a Bachelor of Arts degree and, two years later, a Master of Arts. It was said that, as a university student, he established a reputation for thorough work and accurate scholarship.

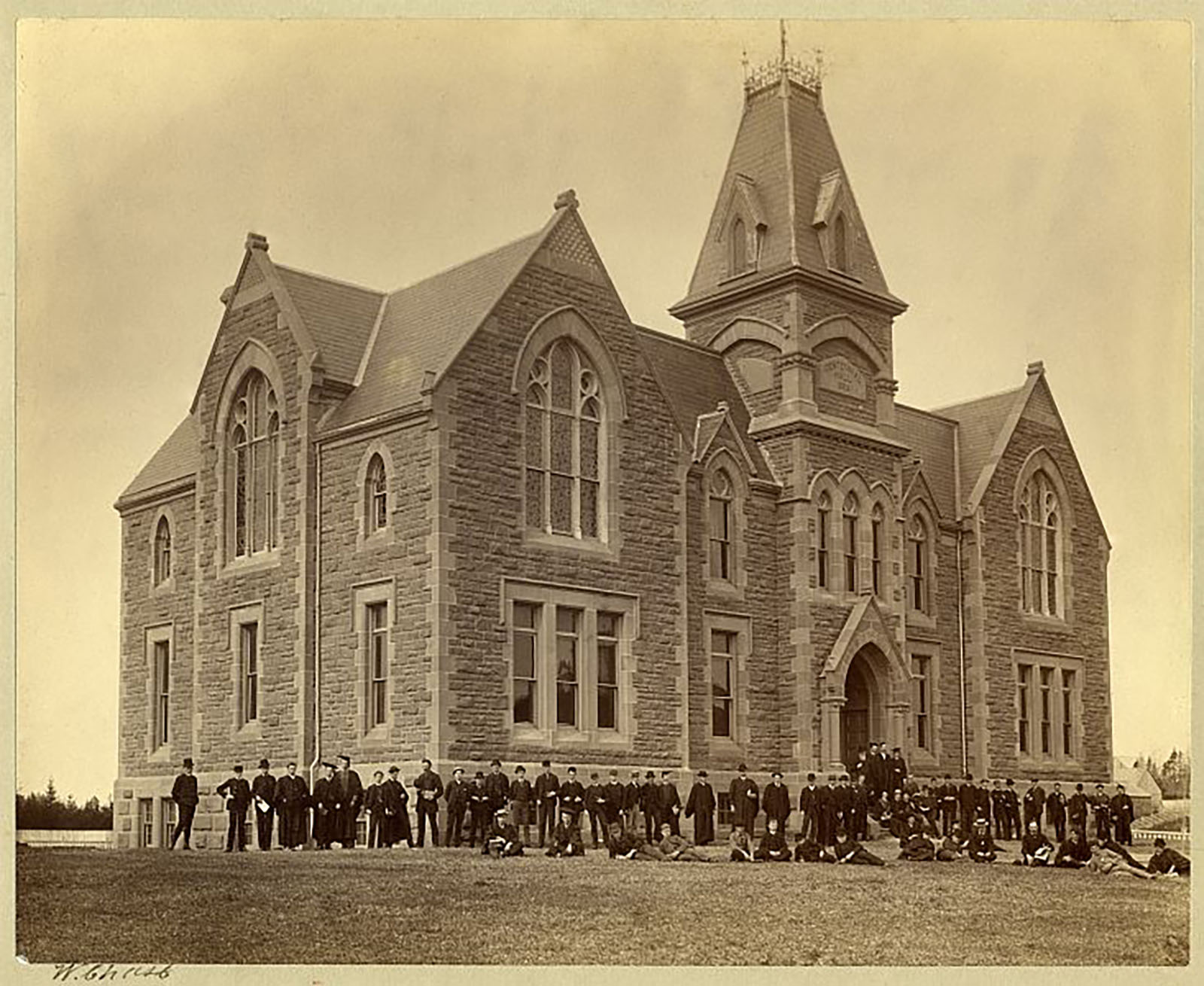

In 1878 he was awarded a Doctor of Laws. That same year, at age 40, he became the third president of Mount Allison University, taking the Chair of Logic and Philosophy. During his 13-year presidency, enrolment more than doubled from 231 to 544 students, and the University’s endowment nearly tripled.

Dr. Inch continued to encourage women to pursue higher education beyond the Ladies’ Academy. One such woman was Harriet Starr Stewart, who became the first woman in Canada to earn both a Bachelor of Arts (1882) and a Master of Arts (1885).

In 1880, Dr. Inch stated, “While other institutions were hesitating in putting the door ajar, Mount Allison had boldly opened its doors irrespective of sex.”

He may not have realized that Lockhart’s graduation was a landmark throughout the British Empire, but his pride was both evident and justifiable.

During his presidency, Centennial Memorial Hall was constructed, as well as new student residences. Mount Allison’s reputation as a centre for music and fine arts also grew, with the creation of a Conservatory of Music connected to the Ladies’ College. It housed 35 teaching and rehearsal rooms and an assembly space named Beethoven Hall.

Under his leadership, the University also began negotiations to acquire the Owens Art Collection and to construct the Owens Art Gallery — now the oldest university art gallery building still in use in Canada.

At various times, he taught rhetoric, French, German, logic, English literature, and mental philosophy. One of his students described him as “a man of broad views, good scholarship, and fine executive abilities.”

In 1891, Dr. Inch left Mount Allison to become the Chief Superintendent of Education for the Province of New Brunswick, relocating to Fredericton. Concurrently, he served as President of the University of New Brunswick Senate.

Dr. Inch was the best-paid employee in the provincial government, with a salary of $2,000 plus $400 for travel expenses — higher than his predecessors due to his “onerous duty of presiding at two meetings of the University Senate each year.”

After 37 years at Mount Allison, Dr. Inch had to transfer his allegiance to the University of New Brunswick — a shift that sparked controversy in several newspaper articles.

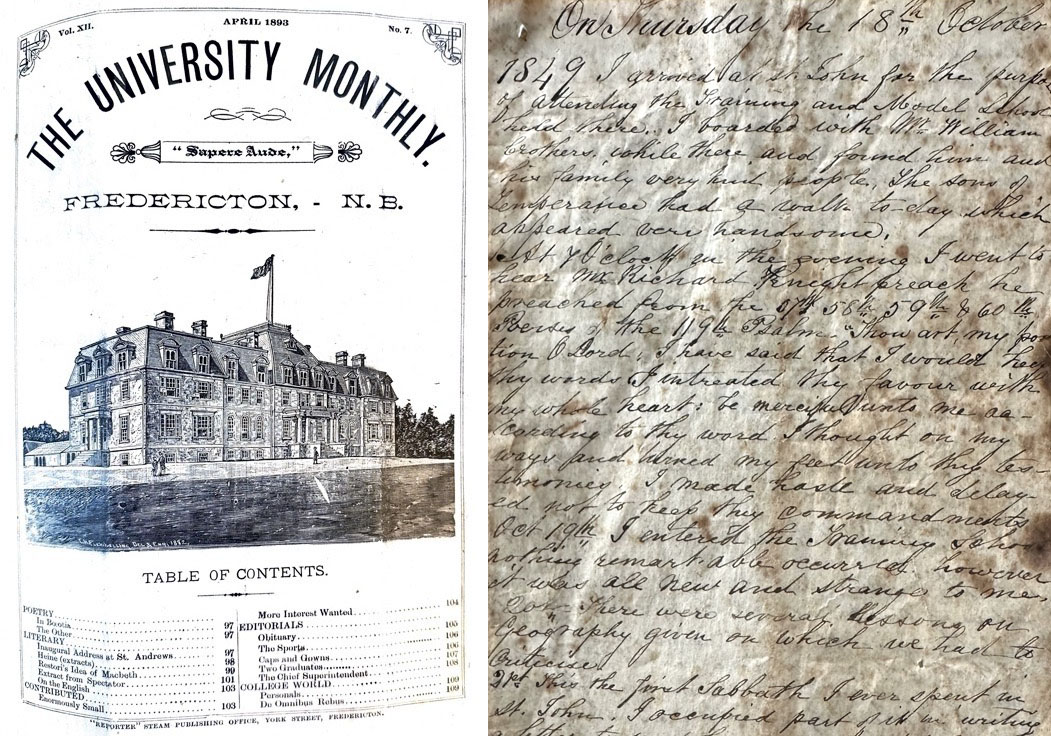

A UNB student writing in the April 1893 edition of The University Monthly alleged that the Superintendent had distributed Mount Allison calendars to high school graduates: “As a member of the Methodist Conference, he is supposed to work entirely for the interests of Sackville. Dr. Inch, as head of the Senate, is supposed to work for the interests of the University of New Brunswick. Is he not then in a false position? It is impossible for a man to sit on two stools so wide apart.”

The Wesleyan came to his defence, describing him as “a very liberal-minded man” and dismissing the accusation that he was indifferent to UNB’s interests. One historian recounted that UNB students once marched to the New Brunswick Legislature and protested in the gallery because Dr. Inch was allegedly advising students to attend Mount Allison. He denied the charges in the Legislative Assembly.

As superintendent, Dr. Inch’s “wisdom and foresight showed quickly.” His proposals included reducing funds for grammar schools that did not meet a minimum number of advanced pupils, instituting compulsory school attendance, and creating examination standards for grammar school leaving and university matriculation.

His greatest challenge was advocating for the consolidation of small school districts. He noted that 490 schools had an average attendance of fewer than 12 pupils, with 76 having fewer than six. Consolidation, he argued, would allow for larger schools and publicly funded transportation for students who lived too far to walk. He believed this would improve teacher salaries and retention. By 1908, only four consolidated schools had been established, the first opening in Kingston in 1904.

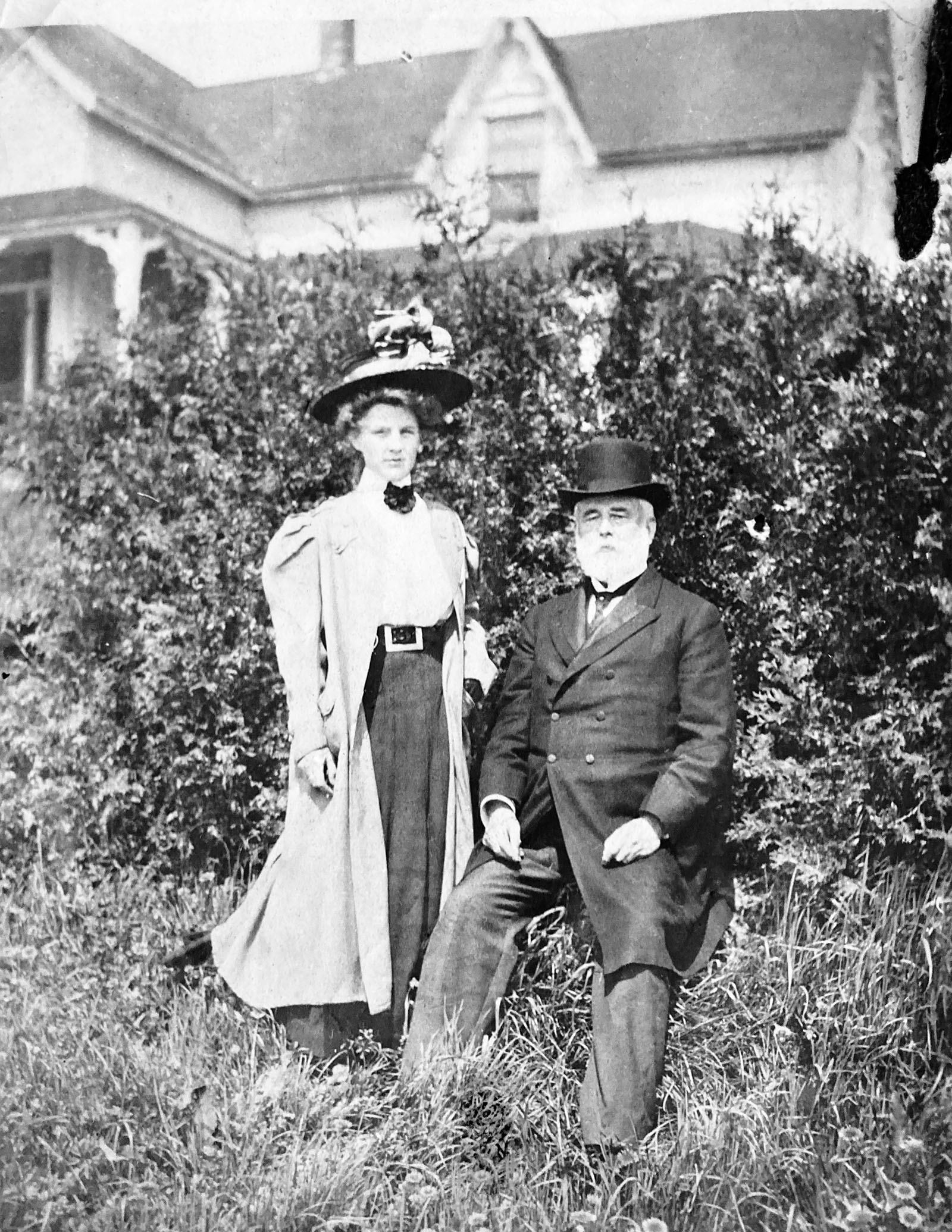

My great-uncle was a visionary ahead of his time; many of his recommendations would not be implemented by the New Brunswick government for decades. Due to failing health, he retired in 1909 and returned to Sackville. He died in 1912 at age 77, leaving one daughter, Annie.

One obituary described him as “a true Christian gentleman of splendid abilities; he was a tower of strength in all that he undertook and a source of pride to his fellow citizens.”

For nearly 60 years, my great-uncle advanced the quality and scope of public education in New Brunswick. He championed progressive education, improved curriculum standards, ensured better teacher training, and expanded access to schooling.

Perhaps his greatest legacy was opening the doors of Mount Allison to women, setting a precedent for other universities across the British Empire. He believed that “young ladies could compete with the sterner sex in either intellectual acuteness or power of acquisition.”

My father, Robert Boyer Inch, was no doubt named after James Robert—and influenced by him. I am a product of my great-uncle’s legacy, passed down through my father, who quietly told me when I was a student at Mount Allison: “You know you can be married and have a career too.” And I did.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to David Mawhinney, Mount Allison University Archivist, for his advice, archival documents, photographs, and friendship. Thanks also to the New Brunswick Legislative Archives, the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, and the University of New Brunswick Archives. I would like to acknowledge Renée Belliveau, who has written extensively about the history and legacy of women’s education at Mount Allison. Finally, I am forever grateful to my father, who preserved the Inch family’s correspondence, documents, and photographs dating back to 1849.